Office of Australian War Graves – delivering on a solemn promise

Like many of you, my family and I share a deeply rooted connection to our military history, having had family members serve in our military at various times.

Having personally served on multiple operational deployments I know what sacrifice means and I remain deeply passionate about DVA’s focus on the respect and recognition of the more than two million Australians who have served in our Defence Force. This recognition consists of commemorative services and information, historical publications and education, and community grants.

For those who made the ultimate sacrifice, the program of official commemorations delivers on a solemn promise made in 1917, with the formation of the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) to mark the graves of the fallen and to care for them in perpetuity.

While walking through our war cemeteries in Australia and inspecting the graves of those who have died during or as a result of their war service, I am mindful of the legacy of those who undertook this work long before my appointment as the Director War Graves.

On 11 November 1949, Admiral Sir Martin Dunbar-Nasmith VC KCB delivered the Imperial War Graves Commission Vice-Chairman’s Remembrance Day Broadcast. He provided an update on the work of the Commission in constructing new war cemeteries and rebuilding First World War cemeteries that were damaged in battles during the Second World War.

It was the scale of the Second World War that really added to the breadth of the Commission’s work. Dunbar-Nasmith wrote of the enormity of the challenge in marking the graves of our war dead ‘from above the Arctic Circle, in the deserts and swamps, in tropical jungles and among the more familiar surroundings of orchard, field and woodland’.

The challenge of this work was ambitious to say the least, taking place across fractured countries and rubbled cities. The Commission went about its work diligently in France, Germany, Norway, Greece, Africa, Italy, Burma, Malaya (to name just a few), taking the view that it was a privilege to mark every grave with a headstone, arrange for its care and upkeep, and ensure that it would never be disturbed.

Dunbar-Nasmith went on to highlight the behind the scenes work in ensuring that: details engraved on headstones or cast into bronze were checked for accuracy with the next-of-kin (wherever possible); the headstone was transported, often over long distances, to the rightful grave; trees, border plants and homely flowers painted a befitting picture among green lawns; these places were cared for and maintained by ex-service members, Commission staff or local labour, in perpetuity.

Today, in Australia, in almost every cemetery in the country, the work of caring for and maintaining war graves is carried out by the Office of Australian War Graves (OAWG) within DVA. In total, OAWG undertakes the care and maintenance, in perpetuity, of 75 Commission war cemeteries and war plots throughout Australia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and the Solomon Islands.

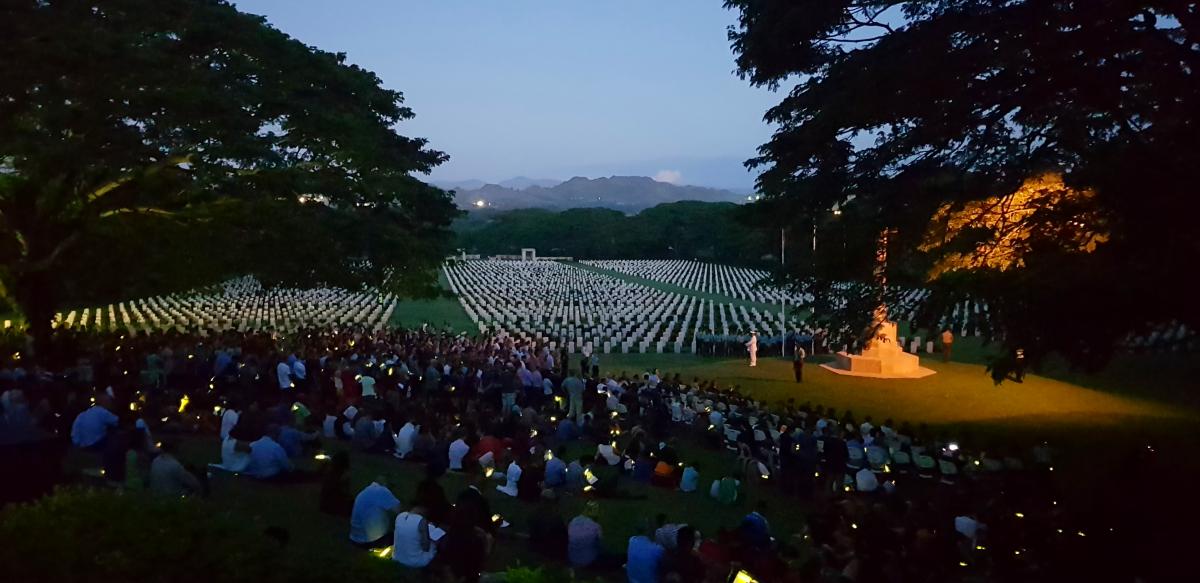

The largest war cemetery is the Bomana War Cemetery in Port Moresby, PNG. It contains the burials of 3,824 Commonwealth service personnel from the Second World War and records the names of a further 750 on the Port Moresby Memorial to the Missing, for those who have no known graves. The Bomana War Cemetery contains more Australian casualties in a single cemetery than any other in the world.

The largest war cemetery in Australia is the Sydney War Cemetery, which contains the graves of 732 Commonwealth service personnel who died in Australia during both world wars, and records the names of a further 750 on the Sydney Memorial to the Missing.

The largest war cemetery in Australia is the Sydney War Cemetery, which contains the graves of 732 Commonwealth service personnel who died in Australia during both world wars, and records the names of a further 750 on the Sydney Memorial to the Missing.

Conversely, one of the most remote sites is perhaps the Geraldton War Cemetery containing 84 graves from the Second World War. This cemetery includes the final resting place of an unknown serviceman whose body washed ashore on Christmas Island some days after the sinking of HMAS Sydney on 19 November 1941.

In total, OAWG cares for the graves and official commemorations of 13,480 service personnel from Commonwealth nations who served, died and were commemorated in Australia during the two world wars. Additionally, OAWG cares for the official commemoration of more than 323,000 Australian service personnel from all wars and conflicts who died during or as a result of their war service. These people may be commemorated in a war cemetery or war plot, a civil cemetery, a lawn cemetery, an ashes placement, niche plaque or on a plaque at one of the ten Gardens of Remembrance, in more than 2,330 locations throughout Australia.

This is a huge responsibility. It is logistically challenging and comes at a financial cost. Though so much time has lapsed since those wars, its impact remains close for many. It’s something I point out when asked why we build memorials to the dead. I also reflect on Dunbar-Nasmith’s words of 1949:

I can only ask in reply: Is it thinkable that our [veterans’] graves, lying scattered over the face of the Earth, should be left unmarked and neglected? And if we believe the sacrifice of all was equal, is it right that those whose graves are lost, should remain unhonoured and uncommemorated?

But there is another reply, which expresses a higher purpose: When we do something for the living, we provide for a material need. When we build in honour of the dead, we enshrine for all time [their] unconquerable spirit.

These words are as relevant now as they were in 1949, and in 1917.

It is a great privilege for me to serve as the Director War Graves and oversee the fabulous work of the staff of the OAWG. All Australians can be proud of the commitment to honour those who have lost their lives in the service of our nation.

Lest we forget.

Sydney War Cemetery, part of Rookwood General Cemetery in western Sydney

Bomana War Cemetery, PNG, Anzac Day 2019