In service to their nation

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the start of post Second World War National Service, which saw more than 290,000 young men called up.

On 8 September 2010, around 2,500 former National Servicemen (or Nashos) marched down Anzac Parade in Canberra and gathered outside the Australian War Memorial. The occasion was the opening by the then Governor-General Quentin Bryce of the National Service Memorial – an elegant water feature made from bronze, sandstone and granite inscribed with the simple words: ‘Dedicated to all Australian National Servicemen and in memory of those who died’.

It was the culmination of years of effort by members of the Nasho community, in particular the National Servicemen’s Association of Australia (NSAA) and the affiliated Officer Training Unit Association (OTU Association).

For many, the creation of the memorial was an important recognition of their service, whether on deployment overseas or, as was more often the case, within Australia. It showed that their service mattered.

Australia had compulsory training in the Citizens Military Forces (CMF) at various times between 1910 and 1945. Since the Second World War, it has had two very different National Service schemes.

The first took place from 1951 to 1959. A total of 227,000 men passed through the scheme, which required six months recruit training in the Navy, Army or Air Force followed by five years as a reservist. Few saw action, though some were deployed on naval ships in Korean waters during that war. They were also at the atomic bomb tests in 1952 at the Monte Bello islands, and in 1956 at Maralinga. RAAF National Servicemen worked on aircraft that had flown through atomic clouds.

In the second scheme, which took place from 1965 to 1972, men aged 20 years were required to register with the Department of Labour and National Service. They were then subject to a ballot, drawn twice a year. If their birth date was drawn, they might be subject to two years of continuous full-time service in the regular Army (reduced to 18 months in 1971). The final five ballots were even televised. Numbered marbles representing birthdates were chosen randomly from a barrel.

A total of 63,735 were called up. Of these, 15,381 served in Vietnam and another 150 in Borneo. The remainder served in support units in Australia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea. Tragically, more than 200 were killed in Vietnam, and two in Borneo. More than 1,200 were wounded and countless others have suffered the consequences of their service.

‘The two eras were very different,’ says Noel Moulder, National Secretary of the NSAA. ‘The first was accepted as a way of life. Every 18-year-old was called up or registered. Mothers and fathers were very proud. The second scheme became a massive objectionable thing.’

In 1987, the late Barry Vicary, a National Serviceman called up in 1965, founded the NSAA in Toowoomba, Queensland. He wanted a better support for Vietnam-era National Servicemen as well as a medal recognising National Service. He later expanded membership to Nashos from the first scheme.

In this, the NSAA has been successful. In 2001, the Australian Government recognised the contribution of National Servicemen to Australia’s defence preparedness with the award of the Anniversary of National Service 1951–1972 Medal. Shortly after, National Servicemen became eligible to receive the Australian Defence Medal in recognition of their completion of required time in service for the respective era.

More recently, the Association has established the National Service Scholarship Foundation, which offers scholarships and grants to advance the professional education, research projects, and skills of medical, dental, nursing, and allied health professionals.

National Servicemen are now entitled to the DVA White Card which enables them to access free mental health treatment for life without having to link their condition to service and assists with treatment of other verifiable conditions caused by military service.

‘This recognition is very important as they served well and faithfully,’ says Ron Brandy, President of the NSAA. ‘A sense that we were now nationally recognised for the service we gave. While a lot of people didn’t resent being called up, they were taken out of their comfort zone, away from their families, compulsorily asked to do military service, and at end were just told “Thanks, your two years are up, see you later”.

He points out that DVA was, at that time, part of a wider problem. ‘It just wasn’t legislatively or culturally geared to accept that these people served equally in all conditions. National Servicemen trained hard and served faithfully and well alongside their regular brothers but had great difficulty in having service-related injuries being accepted by DVA. Thus, the intervention of the late Barry Vicary was pivotal in the journey of recognition of equal service and just compensation for National Servicemen.’

He adds though that the department has changed significantly since then. ‘We very much appreciate the service that DVA provides. We enjoy a cooperative and cordial relationship with the department and its support of the Association.’

The NSAA also persuaded the RSL to accept Nashos as members, and now, in many locations, former National Servicemen hold executive positions at all levels of the RSL. The RSL provides the Association with facilities for social gatherings and formal meetings.

Daryl Bristowe also found it a struggle being accepted not only by civilians but within the Army. He was called up in 1970 and served in Vietnam as a mortarman with the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, and took part in Operation Ivanhoe.

‘We were trying to prove we were the equal of the regular troops so we went in harder,’ he says.

Not that he minded serving in Vietnam. Many Nashos were given the choice of going to Vietnam and he elected to deploy, partly for the extra pay but mostly because he felt it was his turn.

‘My father’s father had been in Gallipoli and on the Western Front and then when the war started against the Japanese, my father was in the CMF and he and his two brothers got involved,’ he says. ‘So when I was called up for National Service, it would have looked bad for me if I’d taken off.’

His main memory of Vietnam was the camaraderie.

‘My Mum baked a fruitcake every week which arrived at 3pm Thursdays,’ he chuckles. ‘Do you know how hard it is to divide a cake into 36 slices using an M16 bayonet with all of your mates staring over your shoulder?’

He went on to spend ten years from 1989 in the Army Reserve then became a volunteer at the Shrine of Remembrance and later Victoria Barracks in Melbourne.

A week or so into recruit training, Nashos in the second scheme were selected to apply for officer training. Of those who applied, only around a third were chosen and of those only two thirds made it through the intensive five-month course at the Scheyville Officer Training Unit (OTU) west of Sydney. Scheyville was a compressed version of the year-long course at the Officer Cadet School, Portsea in Victoria. It was designed to produce the second lieutenants the Army needed in a hurry.

The days and weeks were long and the physical, mental and psychological pressures immense. So much so that it has forged lasting bonds among those who were there, even those who didn’t complete the training. Hence the creation of the OTU Association, which today has around 600 financial members.

Its Chairman Frank Miller, a chemical engineering student at the time, was not happy about being called up in 1965. But he describes his training at Scheyville as a huge asset.

‘It was a pressure-cooker type of situation,’ he says. ‘Coping at first was hard but eventually you learnt to adapt. But now I realise more and more what a huge help it’s been for me. It gave you a greater understanding of what you’re capable of. It taught leadership and discipline – knowing how a leader should present to other people, and how to get the very best out of them.’

After National Service, Frank spent his career in the food business, including 26 years in senior roles with Cadburys.

‘So many Scheyvillians achieved so much in their careers,’ he says. ‘I wonder if I’d have gone as far if it weren’t for Scheyville and the military.’

He says the main aims of the OTU Association are to promote fellowship among its members, to preserve the history of Scheyville and the memory of the eight who made the ultimate sacrifice.

It also seeks to promote leadership skills in Australian youth.

‘We support bodies in the different states that develop leadership in young people. Our prime effort over more than three decades has been sponsoring 16 to 17 year-old men and women to attend the annual Lord Somers and Power House camps in Victoria.

‘I am also very keen on getting Nashos who did not serve overseas signed up for a DVA White Card,’ he says. ‘They may not think they’re entitled but it is terribly important. It covers mental illness and, furthermore, opens the door to DVA.’

Of the 1,881 who passed out of Scheyville, 328 served in Vietnam. One of these was Brian Cooper, Deputy Chairman and former Chairman of the OTU Association. He also sings the praises of Scheyville.

‘If you were of that ilk, it could bring the best out of you,’ he says. ‘It gave you the ability to be cool under stress, multi-task, and keep the big picture in mind.’

He found Vietnam and Army life generally suited him, so he continued to serve for another 20 years, retiring as a lieutenant colonel before enjoying a successful career in executive recruitment.

He points out that in many ways you were better off as an officer in Vietnam.

‘You were so busy, so focused,’ he says. ‘You didn’t have a whole lot of time to be concerned. Whereas the National Service soldier might sit on their sentry post with their mind able to wander. It’s very hard to stay focused and not to think about the dangers.’

Staying in the Army made returning from Vietnam easier too.

‘It was just about getting on with the next job. It may have been different if I’d gone straight back to civilian life. There was that tainted feeling from our involvement in Vietnam. Those diggers could be home with their families within days of being in the jungle. They received no transition training and advice. It caused quite a lot of difficulties.’

National Service Day, 14 February, marks the date the first Nasho marched into a training camp in 1951. So this year marks the 70th anniversary of the start of post Second World War National Service. COVID-19 has curtailed a planned commemorative service at the Australian War Memorial to recognise this important date. However, the NSAA and OTU Association plan to commemorate the 70th anniversary as well as the 50th anniversary of the end of the second National Service scheme in 1972.

More information is available on the following websites:

- NSAA

- OTU Association

- DVA’s Anzac Portal – Conscription

- Australian War Memorial – National Service Scheme

- National Service Scholarship Foundation website

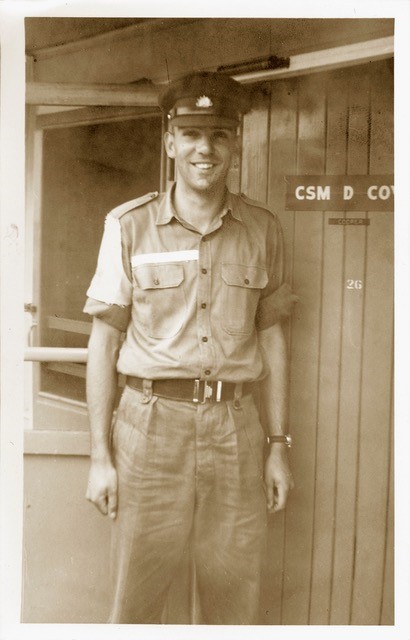

Clockwise from below: National Service Memorial; 12 Platoon, C Company, 19th National Service Training Battalion, Holsworthy, Sydney, March 1956; OTU Association Chairman Frank Miller at an Association dinner, 2018